Motion Planning in robotics refers to mathematically deriving the seqeunce of robot configuration that allows it to achieve a task. It is the study of algorithms and techniques that determine variation in the physical properties of a robot that consequently determine its path of motion. Motion planning is a broad envelope of algorithms applicable to mobile robots, humanoids, manipulator arms and any non-trivial robot type.

Apart from different kinds of robots, few other nuances of motion planning includes non-holonomic constraints, multi-robot planning, physically constrained robot planning and high-dimensional planning. While deriving the robot configuration like angular positions of the actuators of position controlled 6DOF robot arm or robot pose (positio and orientation) for a mobile robot, motion planning algorithms are largely dependent upon the robot model, the world around (obstacles, viable motion paths and configurations), robot physical properties and many more.

Robot Manipulator moving through the green target path

Robot Manipulator moving through the green target path

Introduction

Robotics involves innumerable concepts like motion planning, path planning, robot control and collision detection among others that can be defined as a high-level task or process. However, it is important to define the problem from high-level specifications to low-level machine level descriptions. Motion planning is one of those problem where while at the high level it is making the robot go from a start to an end point, the computational representation would be defining the actuator path at every momemnt, velocity profiling, configuration conversion from task space to actuator space and many more such nuancces.

MP generally addresses the translations and rotations ignoring the robot dynamics and motion-affecting properties. It is the contol system that implements the desired motion (generated from the motion planning algorithms) considering the physical properties of the robot.

For a task like motion from point A to point B on a robot, a motion planning solution generates a plan, represents it as computationally viable solution, declares conditions for compeletion and qualitative expectations.

A robot planning algorithm needs a state-space definition of the robot (basically the different independent variables of a robot) that needs to be defined during the planning, the temporal distrubution of the state-space, initial and final states and the feasibility definition and the optimality conditions.

The general concepts involved in motion planning include geometric representations and transformations of robot state (position, orientation, joint angles), configuration space definitions, sampling-based planners, search-based planners, dynamic motion planning, obstacle avoidance, decision theory and closed-loop online motion planning. Each of these concepts have their own contribution towards handling exceptional planning scenarios or completing more complex definitions of the planning task.

It is important to note that motion planning operates on four broad spectrums - discrete space planning, planning under different constraints, planning in continuous space and planning in uncertainty.

Nuances Of Motion Planning For Robots

Motion planning is a broad field that is not merely confined to generating kinematic configurations but encapsulates several other smaller problems in robotics along.

- Trajectory Planning

A trajectory is a time-sequence of desired position, velocity and acceleration(could also extend to jerk) for every robot actuator. During boundary condition checking across timestamps, this may also define velocity profile to ensure smooth motion.

- Planning Under Constraints

Planning for robots gets tricky with constraints about kinematic, dynamic or other physial properties. Holonomic constraints (where spatial properties like joint angle limits or end-effector position) are easier to abide by for motion planning algorithms. However, the non-holonomic constraints are anything apart from the constraints on geometric coordinates and could be limits on jerk observed, manipulability index limits or otherwise.

- Task Based Planning

While the basic definition of motion planning is generation of configuration sequences for start to end points, on several occassions there are open-ended tasks that are defined in different terms. Coverage problems for robots like vacuum cleaners, warehouse robots, welding robots and force-controlled task executing robots are non-trivial. They often are strategised in terms of intermittent start-end based MP problems that eventually complete the final task.

- Planning for Non-trivial Robots

Planning for redundant robots with extra DOFs or for underwater/zero-gravity robots or unique designs like snake robots or even humanoids is more of a control integrated motion planning task. In such MP problems, it is not possible to defined trajectories or motion profiles without considering the robot stability (dynamic or static), feasibility and optimality of the proposed motion.

Motion Planning Algorithms

Robots are complex structures with considerable disparities between the mathematical models and the actual hardware. Moreover, there are several uncertainties in the environment that can potentially not be represented in the motion planning problem.

Thus, there are different approaches to solving for the desired motion of the robot.

- Sampling-based Planning Algorithms

Sampling-based algorithms deduce the configuration space into huge number of samples and thus breakdownt the complete motion into smaller steps. Paths are constructed between samples that satisfy certain task completion criterion and sequentially the intermittent steps are solved. Conditions on sampling ensure individual optimal steps but do not promise completeness of the task as they solve only at a granular level.

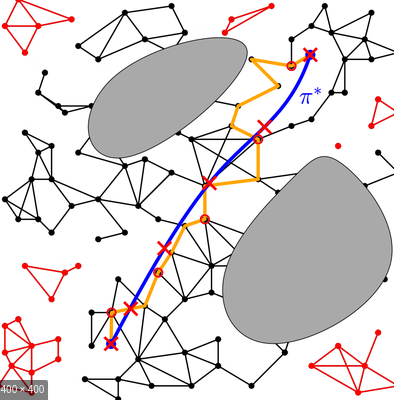

Sampling algorithms are apt for even high-dimensional robot state-space and also suitable for real-time applications. Rapidly Exploring Random Trees(RRT) or PRM(Probabilistic Roadmaps) are the commmon sampling-based algorithms.

RRT Algorithm & PRM Algorithm

- Exact Planning Algorithms

Certain planning algorithms try to solve for motion planning problems directly. Exact algorithms are thorough in their approach and thus find a solution if it exists, for sure. It computes exact path of motion between any two points (terminal or intermittent) that are supposed to solve a part of the problem.

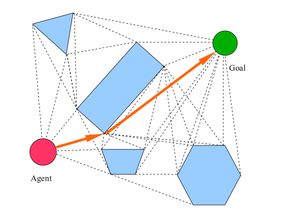

Cellular decomposition or visibility graphs are the most common examples of such algorithms. They are however intractable and computationally expensive, thus not really extensible for high-dimensional problems.

Cellular Decomposition & Visibility Graphs

Cellular Decomposition and Visibility Graphs

- Search-based Planning Algorithms

Search-based algorithms employ general computer-science search algorithms and solve the motion planning task as optimization tasks. Generally, the MP problem is represented as a graph with several grids/lattices and then optimal connections/nodes between the grids that connect the start and desired end points are derived.

Dijkstra, A* and other A* variants are the most common examples of search-based algorithms. While they are again not apt for high-dimensional solutions, they can be applicable to certain tasks like coverage problems and vehicle planning.

A-Star Algorithm & Djisktra’s Algorithm

- Other Planning Algorithms

The above-mentioned algorithms are all model-based operations that need the robot model to determine the feasibility of the algorithm. There has been recent research done in reinforcement learning and other AI technology for motion planning.

Motion Planning Notes

Motion planning is literally all over the place with numerous solutions to a problem, numerous kinds of constraints and limitations and lots of confounding terminology. Advanced robotic systems need to encorporate several of these and thus makes the system too complex to perform reliably.

-

Algorithms like roadmaps (visibility maps and voronoi maps), cellular decomposition and potential fields are generally applicable to possibly all kinds of mobile robots. The assumption here is generally that the robot is a point in space and the actual 3D model is only used for collision checks that decide the feasibility of the path.

-

Any path for robot motion should ideally be formulated by a set of mathematical equations connecting the start and the end through intermittent points. Computers execute instructions in discrete steps and thus any continuous state mathematical representations are still executed in discrete steps by random sampling (in sampling-based algorithms) or pre-defined steps (search-based cellular decomposition and many more).

-

Configuration space or C-space is the set of all possible configurations(a representation of the position of every point on the robot, for a rigid body robot) of a robot. For manipulators, the joint angles and posiitons (for revolute and prismatic joints respectively) for all the DOFs are able to successfully represent it in 3D space and for mobile robots, it is the odometry that defines its setup in space.

Motion planning needs the information about a robot’s valid C-space (valid in the sense where joint position limits exist due to physical structure or otherwise) before proposing a path for motion. Cfree and Cobs represent the obstacle-free and obstacle occupied C-space respectively.

-

The most common high-level tasks for motion planning are coverage, localization, mapping and navigation. There are huge trade-offs made between completeness, optimality, computational expense, control.

-

The formulation of a robot path can be done in joint-space(actuator positions) or task-space(3D world coordinates). While joint-space representations are straighforward, task space representations use homogeneous transformations and pose definitions. Pose definitions for a manipulator end-effector or mobile robot center comprise of positions and orientations. Positions in 2D space are x, y for 2D and x, y, z in 3D. Orientations are represented by quaternions and euler angles.

-

There are certain standard transformations used to define the motion planning results in the desired frames of reference. Affine Transformations are the most common linear transformations that effect all translations, rotations, scaling, shearing and reflections.

Homogeneous transformations are linear transformations that can effect all rotations, shearing, scaling and reflections but not translations. They preserve linearity but not the distance.

Orthogonal transformations are again linear transformations that preserve linearity and distance while only effecting rotations and reflections.

STL Data Structures & Algorithms in C++

STL Data Structures & Algorithms in C++